UCSF Fresno: expanding access to

medical school degrees for Central Valley students

BY BRANDY RAMOS NIKAIDO

Office of Communications — University of California San Francisco Fresno Campus

The UCSF School of Medicine Fresno Regional Campus (UCSF Fresno) extends the reach and impact of the top-ranked UCSF School of Medicine to Fresno, the San Joaquin Valley, and Central California. UCSF Fresno’s mission is to improve health in the region, state, and beyond through teaching, patient care, research, and public service and community partnerships. This includes a commitment to providing high-quality medical education in the region and expanding access to a medical school degree for Valley students.

A great need exists for both primary and specialty physicians in California. In the San Joaquin Valley, the need is even more urgent. There are 47 primary care physicians in the San Joaquin Valley per 100,000 population, in contrast to the recommended 81.

The path to becoming a practicing physician is long and rigorous, taking 11 years or more after high school, depending on the specialty. UCSF Fresno is involved at almost every step of the way – from our longstanding Doctors Academy for high school students who are interested in medical careers, the new SJV-MedBridge pathway for community college students, the recently launched SJV PRIME+ Baccalaureate-to-MD pathway in collaboration with UC Merced, UCSF Fresno residency and fellowship training programs, and UCSF Fresno’s robust continuing medical education portfolio.

To better coordinate and increase the success of existing pathway programs, in summer 2022, UCSF Fresno established the Office of Health Career Pathways (OHCP) within the Department of Undergraduate Medical Education. OHCP provides administrative oversight to all UCSF Fresno pathway programs.

Thanks to long-standing partnerships, state funding, and new collaborations, including with UC Merced, Fresno State, and Valley community colleges, UCSF Fresno is widening the path for local students to become physicians and serve the region that they call home.

UCSF Fresno Doctors Academy

With a focus on addressing the increasing health professional shortage, the Doctors Academy program was established in 1999, by Katherine A. Flores, MD. The program began as a partnership between UCSF Fresno, Fresno Unified School District, and the Fresno County Superintendent of Schools. The first graduating class from the Doctors Academy was in 2003 from Sunnyside High School. The first Caruthers High School graduating class followed in 2010. Middle school programming was introduced through the Junior Doctors Academy program and currently has four school sites that host the program, including Caruthers Elementary, Kings Canyon Middle School, Sequoia Middle School and Terronez Middle School. The UCSF Fresno Doctors Academy programs continue as a partnership with contracting schools. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds are highly encouraged to apply.

All graduating students in the Doctors Academy programs at Sunnyside and Caruthers High Schools received admission to post-secondary institutions. Several Doctors Academy graduates are medical students in the SJV PRIME and three have been accepted into the SJV PRIME+.

“The dedication and commitment from our school sites and community partners are the catalysts that allow us to offer students and their families a wide range of services and opportunities for academic excellence and clinical mentorship experiences,” said Dr. Flores.

“It is because of the collaborative efforts of these strong partnerships that the Doctors Academy students continue to attain their academic goals and are successful applicants to colleges and universities, most with continued aspirations to enter a health profession. We are extremely proud of all our students’ accomplishments and look forward to having them join our Central Valley’s health care provider team in the future.”

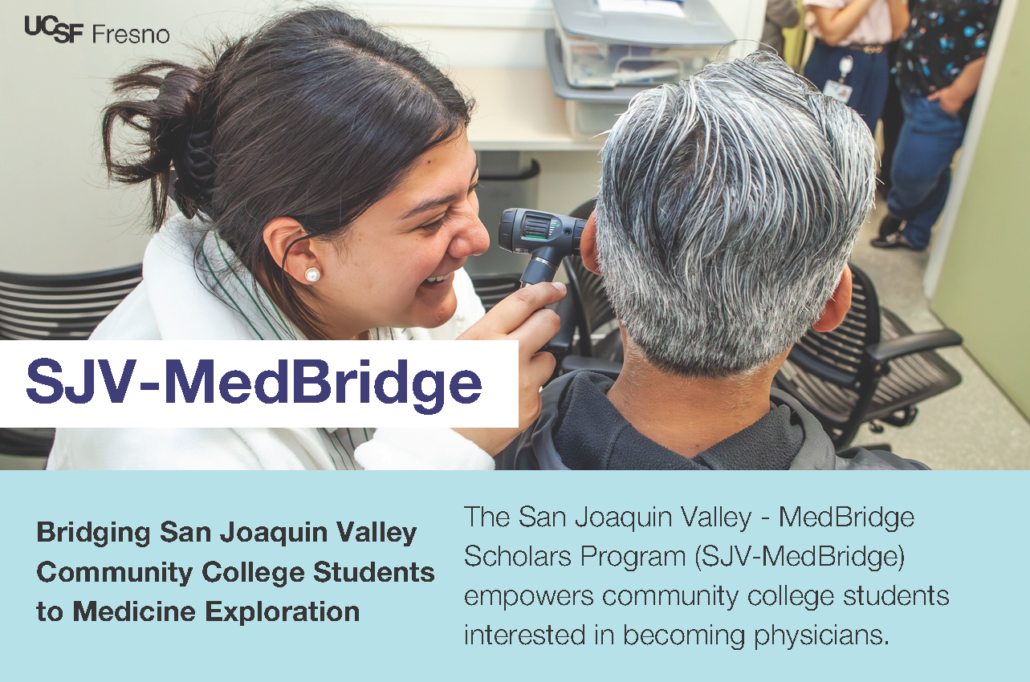

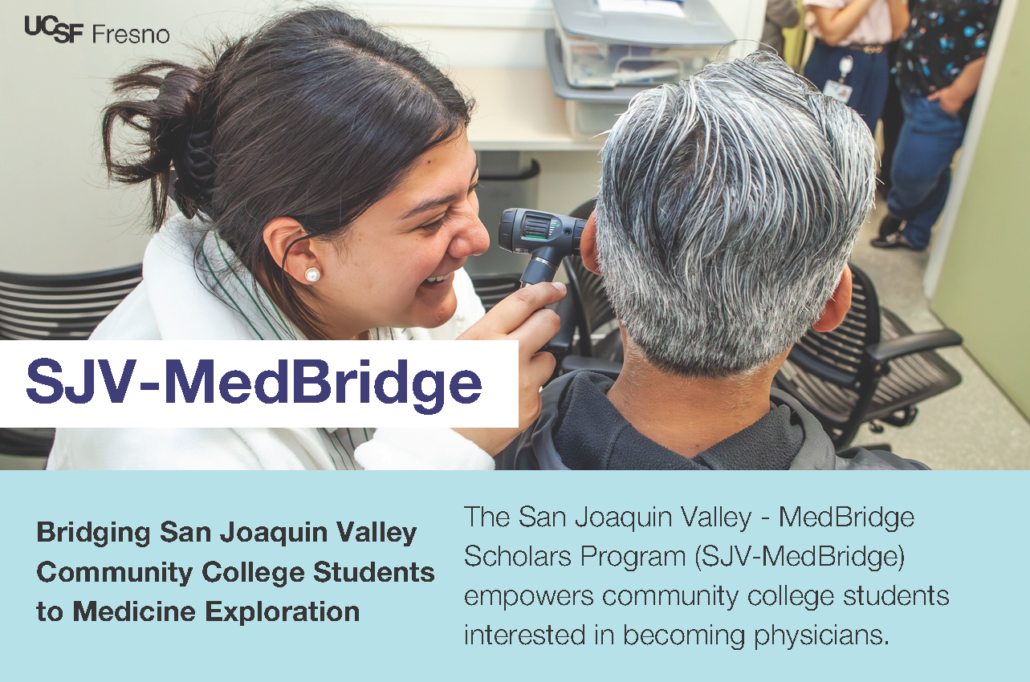

San Joaquin Valley Med-Bridge (SJV-MedBridge)

San Joaquin Valley-MedBridge (SJV-MedBridge) is an outreach-focused program that connects community college students in the San Joaquin Valley to the resources, avenues, and mentors that will help them reach their goals and further allow them to explore the world of medicine.

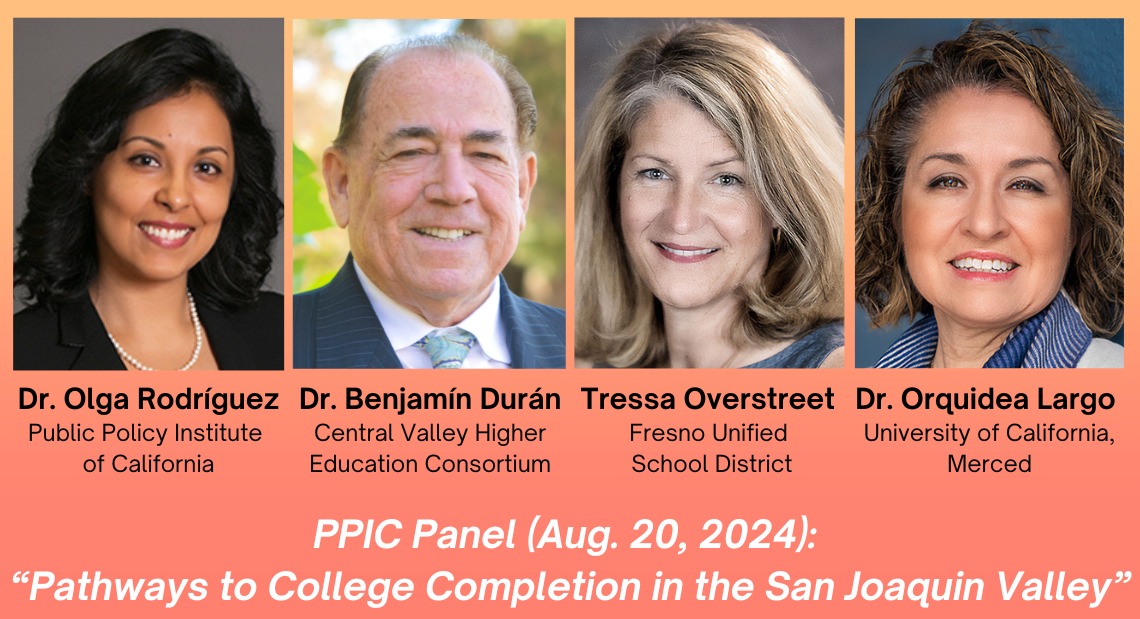

SJV-MedBridge was developed by UCSF Fresno and launched in the fall of 2023, with the encouragement and support of Central Valley Higher Education Consortium Executive Director Ben Duran, EdD, and in partnership with Fresno State, community colleges in the San Joaquin Valley, California Health Sciences University, and multiple medical education programs.

The program was made possible through Senate Bill 40, which was proposed by Sen. Melissa Hurtado (then D-14) in 2021. A native of Sanger, Sen. Hurtado (SD 16) helped fund the establishment of the California Medicine Scholars Program, which is administered by the Foundation for California Community Colleges.

SJV-MedBridge aims to extend and highlight access to various workshops related to medicine and support transfer efforts from community colleges to four-year institutions. The program also encourages and provides networking opportunities to and with experts in the pre-medical community, while fostering a community-focused environment for individuals with a shared interest and passion for medicine.

Each month, students participate in a virtual session and an in-person session, including a simulation day at UCSF Fresno where they learn about CPR, wound care, and ultrasound.

Currently in its first year, the program has enrolled two cohorts for a total of 102 community college students from across eight counties in the San Joaquin Valley.

“We try to eliminate as many barriers as possible to get into SJV-MedBridge,” said Sydney Farnesi, program supervisor. “Qualifications include interest in medicine and completion of 12 units in community college within the San Joaquin Valley. We specifically look for students who do not have a previous bachelor’s degree.”

The goal for SJV-MedBridge is to enroll 50 students each year. Current community college students in the San Joaquin Valley who are driven and seek opportunities to advance into the medical field with a goal of becoming a physician are encouraged to apply to the program. Applications for the next cohort will open in the Summer of 2024.

UCSF San Joaquin Valley Program in Medical Education

The UCSF San Joaquin Valley Program in Medical Education (SJV-PRIME) is a tailored track at the UCSF School of Medicine for students from the Valley who are committed to working with underserved populations in the region at the individual and community levels.

SJV PRIME started in 2011 as a partnership among the UC Davis School of Medicine, UC Merced, UCSF School of Medicine, and UCSF Fresno, with UC Davis serving as the degree-granting institution. UCSF became the degree-granting institution in 2018.

Students in the second class of the UCSF SJV PRIME took part in the 2024 Match, gathering with loved ones, faculty, and staff at a breakfast celebration on March 15 at UCSF Fresno to open the envelopes that would reveal the next step on their paths to becoming physicians.

Match Day takes place annually on the third Friday in March and is the time when soon-to-be medical school graduates across the United States simultaneously learn where they will spend the next several years conducting residency training (the hands-on clinical training under faculty supervision that is required prior to practicing independently).

Seven of the eight SJV PRIME students who participated in this year’s Match will continue their medical education at University of California campuses. Two will stay at UCSF Fresno in Emergency Medicine.

The UCSF Fresno medical residency programs that participated in the National Resident Matching Program received 8,305 residency applications and conducted 1,067 residency interviews for 75 available residency positions.

“We are very excited for our second class of SJV PRIME students on National Match Day,” said Loren Alving, MD, director of UCSF SJV PRIME. “These students are from the Valley, completed two and a half years of medical school in the Valley, and are committed to serving in the Valley. We look forward to great things from them and to one day welcoming them as faculty and as colleagues once they finish their residency and fellowship training.”

SJV PRIME students possess a common desire to provide care and to give back to the communities where they grew up. They also share a calling to promote health equity and mentor Valley students who follow in their footsteps, just as they were mentored.

UCSF Fresno is committed to developing an outstanding physician workforce that reflects Valley communities and improves patient care and access in the region and state. It has long been established that two factors play an essential role in determining where physicians practice: 1) where they grew up, and 2) where they complete their medical education.

By offering Valley students opportunities to complete medical education and training in the San Joaquin Valley, we increase the likelihood they will stay here to practice where they are needed most. Our goal is to recruit, train, and retain highly skilled clinicians and patient advocates for the Valley. UCSF Fresno is the most significant regional contributor to the physician workforce.

Many of our graduates stay in the Central Valley to provide care, continue their education, and teach the next generation.

Recruitment of North Valley high school math and English teachers for dual enrollment qualification begins – info sessions set

Recruitment of North Valley high school math and English teachers for dual enrollment qualification begins – info sessions set